November 21, 2020 – December 31, 2020

Artists on Artists is a novel look at the portraiture genre, whether an artist is painting their own self-portrait or a portrait of their artist colleague.

One subject familiar to most artists is the self-portrait. In this exhibition we examine the self-portrait genre and also portraits of artists by their fellow artists to establish the extent to which, if at all, artists portray their artist friends in a manner different from their own self-portraits.

Conrad Buff was a prolific self-portrait painter. In Self Portrait, Ca.1950, Buff has painted himself staring at the viewer with an uncompromising seriousness. Buff was not quick to give away a mood, and his depiction of himself communicates an intensity that almost makes the viewer self-conscious.

Francis de Erdely, an art professor at USC and other Los Angeles area art schools for decades, gives us a sensitive look at fellow artist Conrad Buff. In this drawing the artist (Buff) is not looking out at the viewer, but rather seems to be gazing inward – almost worried – with a slight look of forlorn vulnerability. de Erdely captures a mood in exquisite detail.

Another example of an artist depicting the mood of a fellow artist is Otis Oldfield’s rendition of his wife, Helen Clark Oldfield, in Purple Sweater from 1933. Helen Clark had been a student of Otis Oldfield, whom she later would marry. Purple Sweater offers us an image of a stern, if not unhappy, wife. Conversely, Helen Clark’s self-portrait from 1924, Herself at 22, depicts a carefree Helen Clark, free from the burdens of marriage.

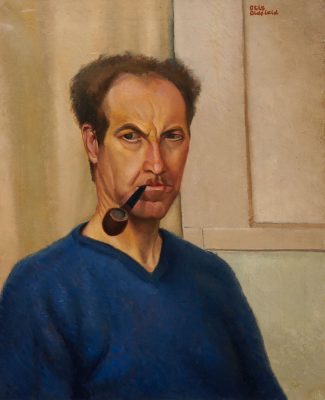

In 1933 Otis Oldfield painted an unflinching self-portrait. Hair on end, and smoking a pipe, Oldfield exudes confidence. Several years earlier, in 1929, Helen Clark Oldfield drew a portrait of her husband and teacher that bears similarities to Oldfield’s own self-portrait. His gaze is again confident, seemingly without care or concern. Helen clearly admired her husband, as borne out by her drawing.

Photographer Edward Weston was known to many of the modernist artists of the 1930s. Evidence of this is Otis Oldfield’s rendition of Weston in Impression of Edward Weston from 1926. It is a less tightly rendered work, unlike Oldfield’s well-known neorealist portraits. Instead it is a shimmering image with planes of color cutting across the subject’s face and clothing, with an almost Cubist perspective. In return, Weston took Oldfield’s photograph in 1928’s Portrait of Otis Oldfield, capturing Oldfield in his French beret with as close to a smile as Oldfield would ever reveal in a portrait. Weston’s portrait of Oldfield is a clear departure from Oldfield’s self-depictions or even the depiction of him by Helen Clark Oldfield.

Then there are self-portraits that reveal an artist’s evident feelings about him or herself. For example, Victor Arnautoff renders himself in a forest in a larger-than-life-size portrait. He seems carefree yet is dressed in a coat, tie and hat, the professional garb of a successful man. His look is difficult to interpret, giving him a mysterious air as he walks through a forest populated, oddly, with horses and riders in the background. What is Arnautoff saying to us… or to himself? The viewer can only wonder.

John Haley painted himself in 1934 at the age of 29 utilizing a Cubist angularity to display himself to the viewer. Using egg tempera for a highly detailed composition, Haley’s self-image is hidden behind a suave mustache and unlikely colors. Haley’s head is positioned askance while his eyes peer out at the viewer with an empty stare – eyes without pupils. What was the artist saying about himself? The viewer is forced to contemplate without ever knowing the truth.

And what was Oliver Grimley thinking? His wide-open mouth and the shocked look on his face convey an artist who did not take himself too seriously but nevertheless felt the compulsion to exhibit himself in a self-portrait. Elongated neck and large ears aside, this self-portrait is a study in extremes. And yes, it must have been intended to illicit guffaws from his audience.

In his self-portrait Peter Krasnow has achieved the uncanny: his eyes follow the viewer no matter at what angle the viewer looks at the portrait. It’s as if the portrait is alive and shockingly following the viewer even when the viewer tries to elude Krasnow’s gaze. There is a depth to his eyes making his self-portrait a wonder to behold.

Whether depicting the artists themselves or their fellow artists, portraits are a view into the soul of the artist – a glimpse at an interpretation of the self or the self of a fellow artist that cries out for explanation and meaning.

Artwork Featured in This Exhibition